My mother, Yukino Asai, is a native of Gunma Prefecture, Japan. Born in 1934, her life began not only in a place but also a time very different from New Jersey where she lives today. Over the decades, she’s told and re-told countless stories from childhood, and I’ve tried to piece together her most vivid memories into a picture of what it was like to be a girl in the early Showa period.

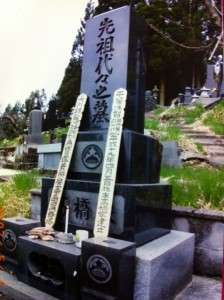

One story that highlights this “another world-another time” aspect of my mother’s childhood concerns her family grave. A traditional Japanese grave is a multigenerational tombstone that has a chamber beneath it in which boxes containing the cremated remains (“cremains”) of deceased family members are placed. Family members regularly visit their tombstone on specific holidays to give offerings (water, incense, flowers, and food) and tidy up the site around the tomb.

Since my first visit as a preschooler, I’ve been to the Asai family grave site more than a dozen times with various members of my Japanese and American families. The tombstone is of average size and style, with little to distinguish it from the other tombstones in the Buddhist temple cemetery. As tradition expects, my aunts and uncles pour water over the tombstone with a ladle, light several incense sticks, lay flowers and sometimes leave tangerines around the stone façade. Oddly, they then repeat the rituals at a spot on the ground about 3 feet from the tombstone, on what looks to be several fist-sized stones that have been pressed into the dirt. Having grown up with these practices, I never thought to ask about the second offerings to the random stones. It’s just what we always did.

Several summers ago, we had the fortune of having several family members in Japan at the same time. Taking advantage of the coincidence, my mother, my two cousins, and my family (my wife Ptarmi, two children, and myself), decided to visit the Asai grave. Sensing that this might be the last time we would be at the grave together, my mother—who in just two years had endured the deaths of her older and younger sisters—asked us to gather around the stones in the ground next to the tomb.

“I think it’s about time I talked to you about our family secret,” my mother began, directing her words to my cousins and me. “Only my siblings and I knew the truth about this secret, and we’ve kept it for nearly 60 years, but now, the memories are fading, so it’s safe for the secret to come out.”

“These stones,” my mother continued, “mark a grave. Beneath them lies a child, the little son of Aunt Jane.” My mother referred to her sister Setsuko—called “Jane” by everyone—who had died from tuberculosis before I was born, more than 50 years ago. I’ve heard many stories about Aunt Jane’s incredible intelligence and courageous civic activities. In the 1950s, she was an outspoken advocate for the fair treatment of laborers and had helped organize a union at the factory where she worked. But she was unmarried and childless, I had thought.

“The boy was illegitimate. He was so cute, always smiling, but had a weak constitution. He died when he was two. The father was a nice enough man but Jane couldn’t marry him…he was Korean.” Historically, people of Korean heritage have not been treated kindly by the Japanese; a Korean-Japanese couple would meet with social intolerance similar to a Black-White couple in the U.S. at the time. So the family secret is as much about Aunt Jane’s affair with a Korean man as it was about her illegitimate baby.

My 7 year old daughter, fluent in Japanese, immediately responded with, “That’s it? That’s the family secret? Big deal!” Thanks to Japan’s enthusiastic embrace of South Korean pop culture today, my kids know nothing about past discrimination against Koreans. Even my mother and much of her generation have at last dropped most of their old biases and are expressing their newly found admiration for (South) Korean history and culture.

So the secret, by today’s norms, turns out to be the typical stuff of a daytime TV soap opera, which is probably why my mother thought it okay to reveal now. And though I relish the fact that we had an old family secret involving a heroic activist aunt’s clandestine affair, her tragic child’s death, and the family tombstone, I am happier that we live in a world where these secrets can be discussed openly as a lesson about the past with our children, who just might grow up with fewer irrational biases and a greater appreciation for diversity than we have.