Disclaimer: Viewing a Solar Eclipse can be dangerous. Do not look directly at the Sun as this can cause pain, damage to your eyes and sight and even blindness

1999 always sounded like a momentous year growing up in the 70s and 80s; the last year with a 1 at the front (until 10,000 of course!), the last year of the nineties and the last year of the 1900s. To many people, it was also the latter bookend of the twentieth century and the second millennium for that matter; maybe 2000 was the proper terminal point, but that just didn’t sound right. 2000 sounded more like a starting point – 1999 had a finality all of its own from sheer numerical content. Prince sang a song about it and there was even a stylish science fiction TV series set in that year. The real 1999, supposedly ending in the biggest party in history, was always going to have difficulty competing with the expectation.

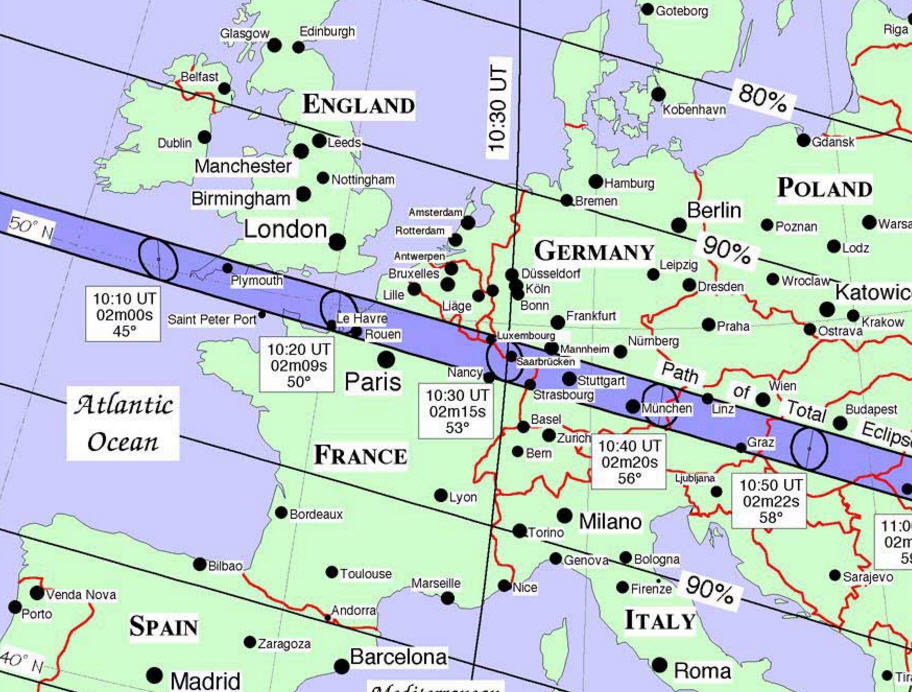

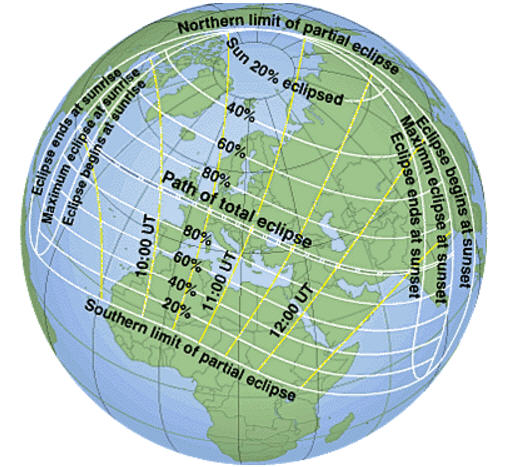

In England, the year 1999’s special role in letting in the Millennium included an extraordinary event that had long been predicted with total certainty – a total eclipse of the Sun, due on 11th August of that year. This momentous interplanetary interplay was entirely fitting to the times and in the long final decades of the twentieth century, the eclipse’s approach was hailed with excitement and curiosity.

A solar eclipse is the blocking of the Sun, to a lesser or greater extent, by the Moon. This only happens rarely as the Moon’s orbit is at a different angle to the plane of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun. The Moon and the Sun are almost exactly, but not quite, the same size in the sky as seen from the Earth as each other; an unusual and striking coincidence.

The Sun is roughly 400 times further away from the Earth than the Moon is. At the same time, the Sun’s diameter is roughly 400 times that of the Moon. As a result, the relative ratios of size and distance mean that they are both roughly a half of a degree in diameter across in the sky. If the situation were any different, solar eclipses would not occur in the way they do.

In fact, the Moon spends the majority of it’s time slightly too far away from the Earth to occupy exactly the same size in the sky as the Sun. As a result, slightly more solar eclipses are what is called “annular” rather than total – that is rather than blocking out the Sun’s disc entirely, the Moon can only occupy most of it but not all, leaving a ring or annulus of the Sun visible behind it.

The Moon’s distance from the Earth varies during its orbit and sometimes it is closer than usual. It is during these points that the Moon is almost exactly the same diameter in the sky as the Sun and the full total solar eclipse can take place.

The distance between the Earth and the Moon is growing over time at the rate of nearly four centimetres per year, or roughly the same speed as the rate at which fingernails grow. At this rate, it will take a very long time, perhaps in the order of a half a billion years or so, before this effect will have an appreciable difference on eclipses, but the general progression will mean more annular eclipses than total.

When, finally, Wednesday 11th August 1999 arrived, there was the dawning realisation that a solar eclipse visible in England would, inevitably, be impaired by less than perfect weather. On the day itself, a colleague and I took some time out from the office to observe it from a nearby park in Portsmouth. At the time, I took with me a hand held mini-cassette tape machine, feeling suitably proud of my technological recording mechanism, to record any such observations.

Nearly eighteen years later, for the first time I’ve gone back and listened to the tape, having to borrow a now virtually obsolete tape machine to listen to it. Such is the march of technological innovation that my ten-year old daughter has never seen a cassette tape machine, of any sort, in operation before.

Though, as an English eclipse, the cloud and modest sunshine meant the event was perhaps less cosmically impressive than it might have been, it’s clear from the tape that we found it to be an absorbing, odd and vaguely disturbing experience. There was already a diminution to the light when we entered the park at around 10.50am that morning, with a noticeable slice missing from a top corner of the Sun’s disk. As the minutes ticked by, the gloom became more profound and the wind driven clouds curled and roiled darkly across the diminished face of our star.

The park where we sat in Portsmouth has an aviary in it, in addition to the normal pigeons, crows and other birds that normally strut and flutter about. As the darkness gathered, unsettlingly the birds noticeably quietened. The absence of this normal background noise of life added to the unease that was slowly building. The light level dropped to around that of twilight, but it was twilight with a distinctively silver tone.

As the cloud whisked across the face of the Sun and Moon in their astral embrace, a shining crescent, thinly blazing, could be glimpsed every now and then. This far from the zone of totality, our eclipse was only ever going to be partial, but it was still an extraordinary sight.

As the maximum point of the eclipse, it grew colder and the wind picked up. The silver twilight, the hush of the life in the park, the gusts and the dropping temperature combined in a surprisingly disturbing, eerie experience. These points were punctuated by the firing of a cannon, presumably on the orders of the City Council, and it was easy during these moments to understand how terrifying an eclipse might have been for people of earlier ages, bereft of our clear understanding of the Solar System’s mechanics and with only their imaginations to play out on what might be happening.

Soon though, the normal daylight returned and for some minutes the rising light levels manifested as pretty and unpredicted pink and orange shades on the clouds near to where the Sun and Moon passed in the sky. Once again, all was well.

America’s eclipse on 21st August 2017 looks very promising; bisecting the United States, it is almost certain to have stretches of clear, or at least clear enough, skies for an uninterrupted total eclipse. Millions of people should be able to enjoy this extraordinary spectacle and for those of us not in the USA, it can be viewed on the NASA website at https://eclipse2017.nasa.gov/. If you can, do experience it – but keep your eyes safe!

Image sources:

https://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEmono/TSE1999/TSE1999Map/TSE1999Europe.jpg

https://magnetograph.msfc.nasa.gov/outreach/girlscouts/eclps_1999.html

https://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEmono/TSE1999/TSE1999.html