By Adam D.A. Manning (@AdamManning)

The evolution of life is an endlessly fascinating subject to study. The richness of the ever-changing chronicle of living things is part of the beauty of nature and in recent decades a new approach to viewing the evolution of the terrestrial vertebrates (that is the reptiles, birds, and mammals) has emerged which challenges our conventional categories.

Reptiles, birds, and mammals have long been the three main groupings of backboned animals that fully live on (or above in the case of birds) the land. This is derived from our everyday observations of these animals as they are today, but the fossil record reveals a somewhat different tale.

The earliest reptiles evolved from their amphibian ancestors between 310 and 320 million years ago, in the late Carboniferous period. Shortly after the emergence of the reptiles (known as the sauropsids), a new group called the synapsids evolved from them, splitting the amphibians’ descendants in two.

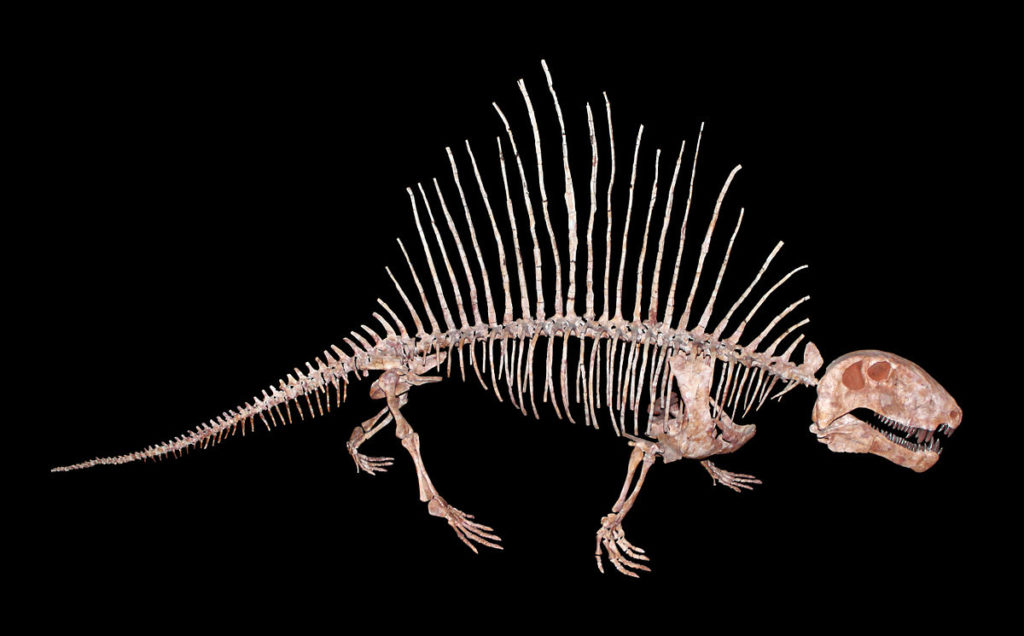

For a while this divergence seemed to be favouring the synapsids. This is the group of animals that includes mammals (and therefore humans as well), but it also includes a varied assemblage of all sorts of other species. The earlier synapsids included the familiar Dimetrodon, which had a large “sail” on its back and was roughly four metres long. It was a top predator for its time, that being the early Permian period and animals like Dimetrodon later evolved into the therapsids.

Therapsids were a very diverse group of animals, such as Lystrosaurus from the early Triassic, which became one of the most successful vertebrate land animals of all time. Another remarkable species from the later Triassic was Lisowicia, one of the most massive animals of its time, comparable in size to an elephant. The ancestors of the mammals within the therapsids were in a group called the cynodonts, which included the fearsome wolf-sized predator Cynognathus, again from the Triassic.

Whilst the synapsids seemed the more dominant since diverging from their more reptilian ancestors, something was happening to challenge that dominance during the Triassic. The sauropsids were diversifying into all sorts of new types, including the dinosaurs and the crocodylomorphs, that is the crocodiles and all their ancestors. Crocodiles and the group they belong to have been an enormously successful family of animals, with an abundant range of all manner of different types, far more than those we are familiar with today. There were also numerous aquatic types within the sauropsids, such as the dolphin like ichthyosaurs, and flying and gliding species as well.

The catastrophic extinction event at the end of the Permian and the start of the Triassic is well known as causing the extinction of a significant majority of all species. There was another, albeit less cataclysmic, extinction event at the end of the Triassic and start of the Jurassic, roughly 200 million years ago. The Triassic-Jurassic extinction saw the demise of all the therapsids apart from the mammal-like cynodonts.

The Jurassic period and the Cretaceous that followed it saw the sauropsids in the ascendant, causing the Mesozoic to often be referred to as the Age of the Dinosaurs. Whilst the therapsids were limited to those cynodonts that had survived, they went onto evolve into a great many diverse species, including the true mammals and their ancestors.

Mesozoic mammals and their relatives are often thought of as small, unobtrusive shrew or mouse like animals, and many were. Yet here too, there was a surprising divergence of body types. These included tree-climbers, species that glided and animals that had a burrowing lifestyle, like moles. Another extraordinary Jurassic animal from this group was the beaver-like Castorocauda, which was adapted for living partially in the water, and had a pelt of fur. One of the largest Mesozoic mammals was the Cretaceous carnivore Repenomamus, and there is evidence that it ate dinosaurs.

For all this mammalian diversity, there is no doubt that the sauropsids dominated throughout the Jurassic and the Cretaceous. The mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous that included all the non-avian dinosaurs was only a temporary setback as the birds, as descendants of the dinosaurs and part of the sauropsids, not only survived but went on to thrive.

Including the birds, there are today more species of sauropsids than synapsids. Whilst it is tempting to think of the time after the Mesozoic as an age of mammals, it is perhaps more valid to think of it as a continuation of the age of sauropsids, just as it has been for the last 200 million years or so. At a personal level, most of the wild animals most people will see are sauropsids, rather than synapsids. The reptiles and birds we see today are really part of the sauropsids, whilst the mammals, including us, are the only survivors of a much larger group, the synapsids.

The fossil record helps us to understand the story of life in all its richness and can often challenge preconceptions based on our snapshot of living things as they are today, showing us new relationships and connections and enhancing and deepening our appreciation and love of the natural world.

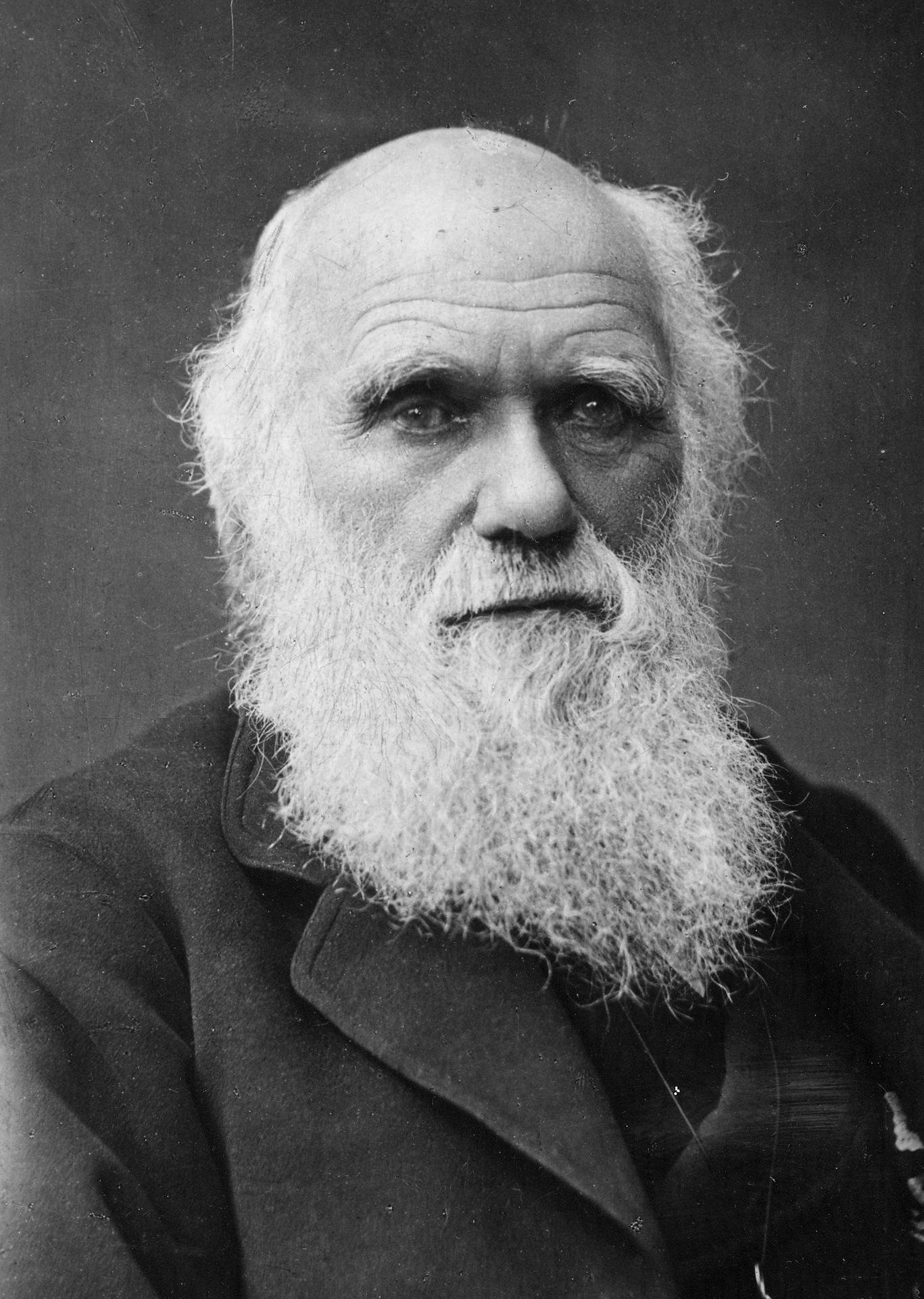

So striking was the example of the peacock in suggesting that there was more to evolution than just a struggle for existence that in 1860, Darwin wrote, “[T]he sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick!” Peacocks and other examples of such displays lead to Darwin developing his ideas on sexual selection in a later volume entitled The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex in 1871, yet this aspect of his theory of evolution has never received the same degree of attention as the concept of natural selection by adaptation, in part due to resistance by some of his original supporters.

So striking was the example of the peacock in suggesting that there was more to evolution than just a struggle for existence that in 1860, Darwin wrote, “[T]he sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me sick!” Peacocks and other examples of such displays lead to Darwin developing his ideas on sexual selection in a later volume entitled The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex in 1871, yet this aspect of his theory of evolution has never received the same degree of attention as the concept of natural selection by adaptation, in part due to resistance by some of his original supporters. Sexual selection plays a role in mammal courtship as well. In many species, the larger a male is, the more likely he is to mate. Females generally choose larger males to mate with, presumably on the basis that larger babies are more likely to survive, dominate others and then mate in turn. Male characteristics that suggest larger size add to their attractiveness to females. Male koalas and hyenas, for example, give out bellows and barks to attract a mate and it seems the deeper the sound, the more attractive it is to females as this suggests a larger male.

Sexual selection plays a role in mammal courtship as well. In many species, the larger a male is, the more likely he is to mate. Females generally choose larger males to mate with, presumably on the basis that larger babies are more likely to survive, dominate others and then mate in turn. Male characteristics that suggest larger size add to their attractiveness to females. Male koalas and hyenas, for example, give out bellows and barks to attract a mate and it seems the deeper the sound, the more attractive it is to females as this suggests a larger male. It is also possible that partial bipedalism is a characteristic of our older ancestors, including the joint ancestors of chimpanzees and humans, and that chimpanzees are the ones that have changed the most by becoming functionally quadrupedal. Gibbons, for example, are often bipedal when climbing in trees and walking along thin branches and provide an illustration of the nature of our possible original partial bipedalism. According to this theory, human ancestors were already partially bipedal when living an arboreal lifestyle and perfected this when travelling on ground level, whilst chimpanzees took a different course.

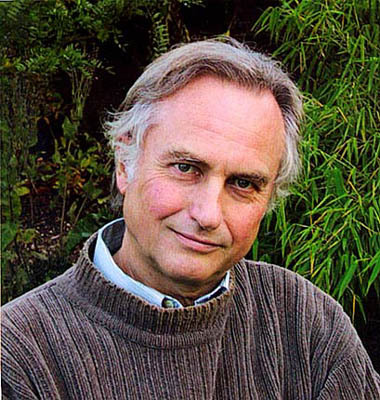

It is also possible that partial bipedalism is a characteristic of our older ancestors, including the joint ancestors of chimpanzees and humans, and that chimpanzees are the ones that have changed the most by becoming functionally quadrupedal. Gibbons, for example, are often bipedal when climbing in trees and walking along thin branches and provide an illustration of the nature of our possible original partial bipedalism. According to this theory, human ancestors were already partially bipedal when living an arboreal lifestyle and perfected this when travelling on ground level, whilst chimpanzees took a different course. Richard Dawkins has suggested that it might be as simple as that – standing upright became an attractive trait at some point amongst our ancestors. In his book The Ancestor’s Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Life he suggests that at some point in our evolution, those who engaged in the new “fashion” of standing and walking on two legs were attractive to potential mates, gained reproductive success and left descendants whereas, over time, those who weren’t bipedal failed to mate. As described above, this trait could quickly become established and grow more and more pronounced as the generations passed by. At least initially, the practical utility of being bipedal may have been irrelevant.

Richard Dawkins has suggested that it might be as simple as that – standing upright became an attractive trait at some point amongst our ancestors. In his book The Ancestor’s Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Life he suggests that at some point in our evolution, those who engaged in the new “fashion” of standing and walking on two legs were attractive to potential mates, gained reproductive success and left descendants whereas, over time, those who weren’t bipedal failed to mate. As described above, this trait could quickly become established and grow more and more pronounced as the generations passed by. At least initially, the practical utility of being bipedal may have been irrelevant. may have arisen as a result of many of these factors acting together; it is unlikely that it was just one cause. For example, perhaps sexual selection started the process but when the practical advantages gave our bipedal ancestors a better chance of survival, the change really took hold. The incompleteness of the fossil record and the generally interpretative context of much of these issues suggest it is possible that there will never be a definitive answer as to how or why humans became fully bipedal. As more fossils are uncovered, more will be learned about our ancestors and our evolution and it will be fascinating to see the story unfold.

may have arisen as a result of many of these factors acting together; it is unlikely that it was just one cause. For example, perhaps sexual selection started the process but when the practical advantages gave our bipedal ancestors a better chance of survival, the change really took hold. The incompleteness of the fossil record and the generally interpretative context of much of these issues suggest it is possible that there will never be a definitive answer as to how or why humans became fully bipedal. As more fossils are uncovered, more will be learned about our ancestors and our evolution and it will be fascinating to see the story unfold.

As a possible apocalyptic scenario, climate change is sometimes ranked alongside, or even superior to, nuclear war in severity. Headlines tell us that the ever escalating concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will relentlessly push the temperature higher, unleashing all manner of dangers and adversity, threatening our way of life and harming Earth’s ecosystems. Sometimes it seems so terrifying that we are taken beyond the point of caring and prefer a blissful ignorance as to what awaits us.

As a possible apocalyptic scenario, climate change is sometimes ranked alongside, or even superior to, nuclear war in severity. Headlines tell us that the ever escalating concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will relentlessly push the temperature higher, unleashing all manner of dangers and adversity, threatening our way of life and harming Earth’s ecosystems. Sometimes it seems so terrifying that we are taken beyond the point of caring and prefer a blissful ignorance as to what awaits us. o look into this with an open mind and to use respected sources of information. It’s obvious that climate change and climate science generally are highly complex. There is a lot of information available and whilst it is tempting to wish for a simple one page summary, there are so many variables covering such a range of factors that concise overviews are in danger of being misleading.

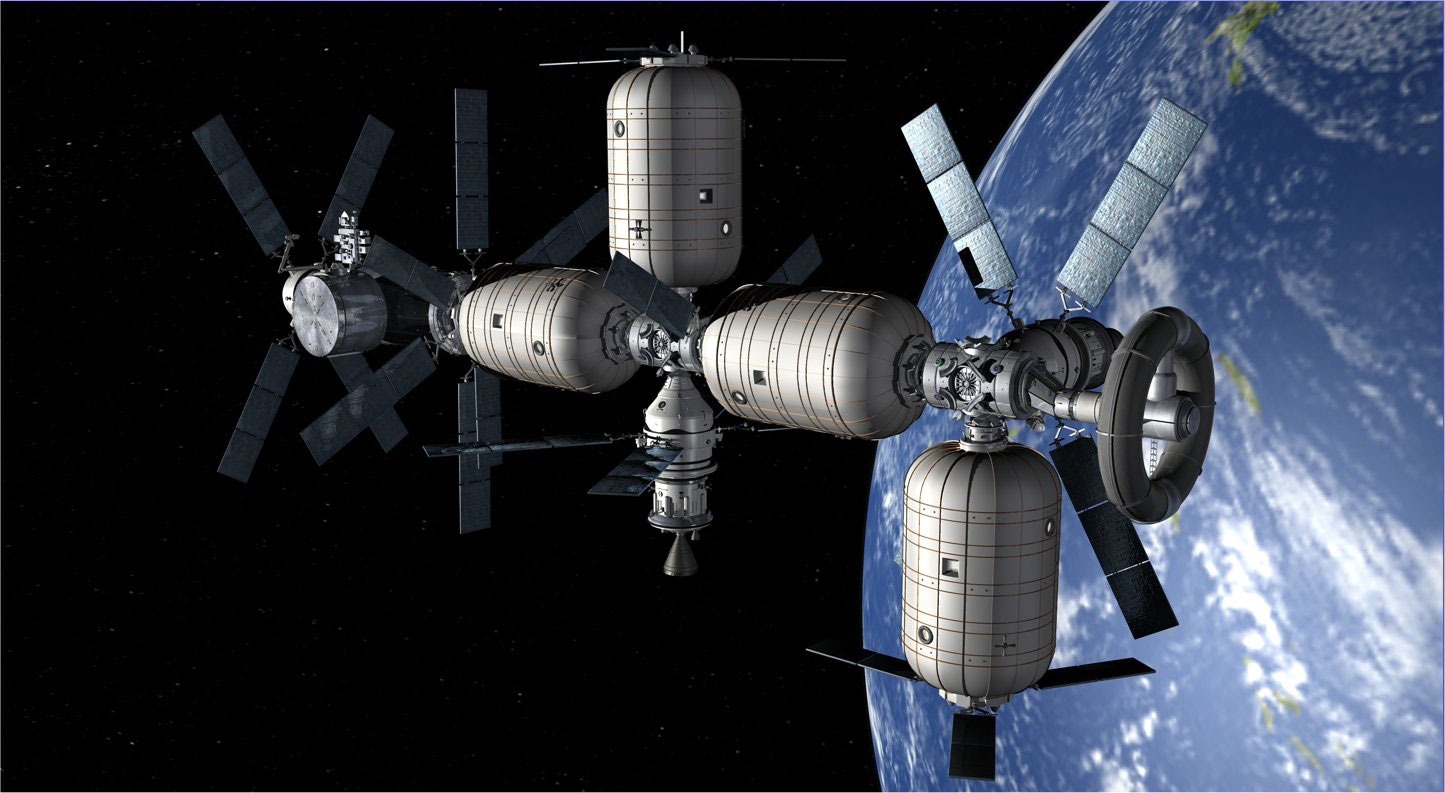

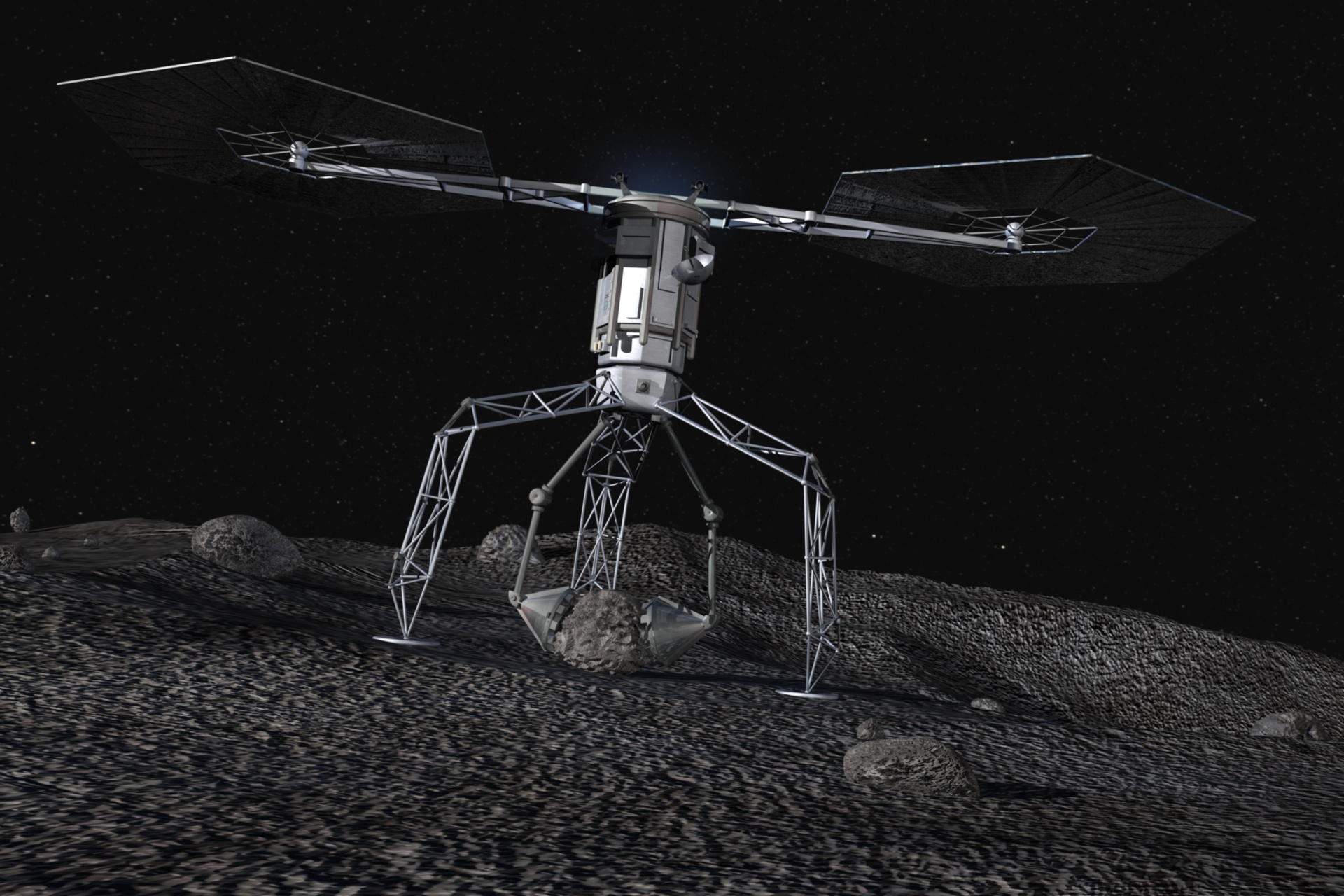

o look into this with an open mind and to use respected sources of information. It’s obvious that climate change and climate science generally are highly complex. There is a lot of information available and whilst it is tempting to wish for a simple one page summary, there are so many variables covering such a range of factors that concise overviews are in danger of being misleading. Originally proposed by Dr. Peter Glaser in 1965, the concept involves satellites in orbit converting solar energy from our Sun and converting this into a form that is then transmitted down to a receiving station on the Earth’s surface below, either by microwave or laser transmission. The advantage over solar panels on Earth is that solar energy in space is effectively continuous; the weather or the day/night cycle cannot interfere. Without the barrier of the atmosphere, solar energy is more powerful as well. SBSP seeks to directly tap the endless and enormous energy of our Sun and put it to use here on Earth.

Originally proposed by Dr. Peter Glaser in 1965, the concept involves satellites in orbit converting solar energy from our Sun and converting this into a form that is then transmitted down to a receiving station on the Earth’s surface below, either by microwave or laser transmission. The advantage over solar panels on Earth is that solar energy in space is effectively continuous; the weather or the day/night cycle cannot interfere. Without the barrier of the atmosphere, solar energy is more powerful as well. SBSP seeks to directly tap the endless and enormous energy of our Sun and put it to use here on Earth. In the decades that have followed, new studies have returned to the idea. The tantalising prospect of cheap, abundant energy means interest has never entirely disappeared. One common theme is that no fundamental breakthrough in science is required to deliver SBSP; the challenges are those of scale and cost. As well as the huge infrastructure required, another issue is the very large number of launches from Earth that would be required and their resultant costs. One suggestion on how to tackle this is to use materials taken from the Moon’s surface as the building blocks for the power satellites, thus cutting down on the number of launches from Earth’s high gravity well.

In the decades that have followed, new studies have returned to the idea. The tantalising prospect of cheap, abundant energy means interest has never entirely disappeared. One common theme is that no fundamental breakthrough in science is required to deliver SBSP; the challenges are those of scale and cost. As well as the huge infrastructure required, another issue is the very large number of launches from Earth that would be required and their resultant costs. One suggestion on how to tackle this is to use materials taken from the Moon’s surface as the building blocks for the power satellites, thus cutting down on the number of launches from Earth’s high gravity well. More recent consideration focuses on the use of new techniques and technologies to reduce the costs required in creating a viable SBSP system. The original studies envisaged armies of workers in space being required to assemble the power satellites; modern studies note how robotics can be used instead, especially when combined with 3D printing techniques. John C. Mankins’ book, The Case for Space Solar Power is an accessible and fascinating look at the development and current state of studies on SBSP.

More recent consideration focuses on the use of new techniques and technologies to reduce the costs required in creating a viable SBSP system. The original studies envisaged armies of workers in space being required to assemble the power satellites; modern studies note how robotics can be used instead, especially when combined with 3D printing techniques. John C. Mankins’ book, The Case for Space Solar Power is an accessible and fascinating look at the development and current state of studies on SBSP. As well as the power satellites, which would still be very large even with the application of modern techniques, the receiving stations on Earth would be huge as well. To collect the radiation at ground level will require stations that are estimated to be, again, over one kilometre in diameter. The safety of the microwave or laser transmissions to Earth from the power satellite is also another key issue. Advocates suggest these would be at such a low level that it would be safe for birds or aircraft to fly through; opponents are not so sure.

As well as the power satellites, which would still be very large even with the application of modern techniques, the receiving stations on Earth would be huge as well. To collect the radiation at ground level will require stations that are estimated to be, again, over one kilometre in diameter. The safety of the microwave or laser transmissions to Earth from the power satellite is also another key issue. Advocates suggest these would be at such a low level that it would be safe for birds or aircraft to fly through; opponents are not so sure.